This may not be unique among adopted people, but I don’t really think about it – being adopted – much at all. The only times it comes to mind is when I’m asked about my family medical history (not known) or if I’m with my mom and told we look a lot alike. I used to get that comment with my dad even moreso, but the response was and is always the same: I laugh and smile as I divulge my little ‘gotcha’ secret, “I’m adopted!”

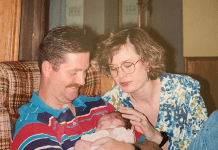

The truth is, though, it’s not a secret, and never has been. From my earliest memories, I always knew I was adopted and had absolutely no questions or trauma about it. I grew up the only child of a loving family who were unfortunately not able to have their own children biologically, after a stillbirth and a late miscarriage. Many of us probably don’t know or certainly don’t fully appreciate our mother’s pain and trials in life until we become mothers ourselves and glimpse a peak at everything they’ve been through, mostly for us. It’s humbling and grounding because when you become a mother, you suddenly just know, every single thing you would do to protect your child and (try to) keep them happy, and if I’m being really honest, that might make you feel guilty for all those times you were selfish and acted like a jerk to your own parents. At least that’s what happened to me. Major guilt. And also major appreciation in a way I just didn’t get before.

For a brief time as a teenager, when I didn’t have major guilt or the sensitivity to know better, I got curious and started asking about my biological parents. I hadn’t really been told much because there wasn’t much to share. I knew I was born in Lafayette and that we didn’t have names or much other information because it was a closed adoption. So obviously, the very invitation of a mystery to solve! This sudden teenage interest in my past upset my mom a little; I suppose I would feel a little anxious too if one of my girls decided they wanted to “find a different family,” as I can imagine that’s how my new curiosity might have been perceived. Nothing happened. I read some old papers my mom had kept from the adoption attorneys, a few boxes ticked on a family medical history form, a brief synopsis of unidentifying information about their career backgrounds, and that was it. Nothing else to go on. The mystery was stuck in time. The attorneys had since retired and their office was no longer open. We were left to wonder. Our (completely loosely informed) guess is that they were both professors, perhaps at UL. But to be clear, that’s a guess based on very limited information. It’s been more than two decades since that went nowhere, and still no closer now. The only new intel I’ve found, through 23andMe, and probably the biggest unexpected surprise, is that I’m over 25 percent Ashkenazi Jew, which would mean one of my biological parents was at least 50 percent, and based on a little deeper research, I probably have an ancestor who was a holocaust survivor.

For a brief time as a teenager, when I didn’t have major guilt or the sensitivity to know better, I got curious and started asking about my biological parents. I hadn’t really been told much because there wasn’t much to share. I knew I was born in Lafayette and that we didn’t have names or much other information because it was a closed adoption. So obviously, the very invitation of a mystery to solve! This sudden teenage interest in my past upset my mom a little; I suppose I would feel a little anxious too if one of my girls decided they wanted to “find a different family,” as I can imagine that’s how my new curiosity might have been perceived. Nothing happened. I read some old papers my mom had kept from the adoption attorneys, a few boxes ticked on a family medical history form, a brief synopsis of unidentifying information about their career backgrounds, and that was it. Nothing else to go on. The mystery was stuck in time. The attorneys had since retired and their office was no longer open. We were left to wonder. Our (completely loosely informed) guess is that they were both professors, perhaps at UL. But to be clear, that’s a guess based on very limited information. It’s been more than two decades since that went nowhere, and still no closer now. The only new intel I’ve found, through 23andMe, and probably the biggest unexpected surprise, is that I’m over 25 percent Ashkenazi Jew, which would mean one of my biological parents was at least 50 percent, and based on a little deeper research, I probably have an ancestor who was a holocaust survivor.

So, what does it all mean?

Nothing really, which is why I don’t think about it much. That information didn’t matter to the life I led as a teenager, and it certainly doesn’t matter now. It doesn’t change anything. The Nana and now Heavenly Papa Danny my daughters know, along with my husband’s parents, are the only grandparents they need to know – we are loved beyond measure, and we are so fortunate to have their presence and support in our lives. My mom and I haven’t always had the easiest relationship – we’re different people, with different motivations and interests – likely one of the only biological deviations that does matter. But my mom is also the first person who will come help in a crisis, or even a perceived crisis, as I’m sure a lot of people’s moms do as well. Our relationship probably speaks to the classic nature vs. nurture argument. But it’s not either/or, it’s both, whether you’re adopted or not. Isn’t that the only really important measure of our relationships with our parents – that we can call them for comfort and help and they’ll practically drop everything to be there for us? That is both nature and nurture. I know I don’t show enough gratitude often enough to really express appreciation for that confidence of comfort, safety, and reliability that our parents provide, but it’s always there, and I can’t imagine it would be any different because of a few similar chromosomes.

About the Author

Desi Comeaux is a native of Lafayette, mom to two young girls, married to amazing husband David for 15 years, and still trying to figure out how to do it all (Ha!).

Desi Comeaux is a native of Lafayette, mom to two young girls, married to amazing husband David for 15 years, and still trying to figure out how to do it all (Ha!).